- Home

- Caroline Bird

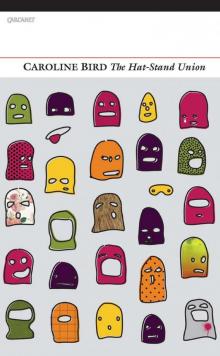

The Hat-Stand Union

The Hat-Stand Union Read online

CAROLINE BIRD

The Hat-Stand Union

For my Mum

Acknowledgements

‘The Fun Palace’ was commissioned by Winning Words as part of the Art in the Park programme for the London Olympics 2012.

‘Public Detectives’ was first published in Joining Music with Reason (Waywiser Press, 2010), an anthology edited by Christopher Ricks.

Versions of ‘Hey Las Vegas’ and ‘Thoughts inside a Head inside a Kennel inside a Church’ were first published online by Poetry International, and ‘Break-up Party’ was published in Fourteen.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

1 Mystery Tears

Sealing Wax

Username: specialgirl2345

Mothers

Snow Hotel

Unacceptable Language

Mystery Tears

Method Acting

The Dry Well

A Dialogue between Artist and Muse

Hey Las Vegas

Genesis

9 Possible Reasons for Throwing a Cat into a Wheelie Bin

Day Room

Faith

Dolores

There Once Was A Boy Named Bosh

Thoughts inside a Head inside a Kennel inside a Church

The Only People in Paradise

Fantasy Role-Play

Empty Nest

Spat

How the Wild Horse Stopped Me

The Island Woman of Coma Dawn

2 The Truth about Camelot

Prologue

I A Confident Local Youth

II Some Last Words

III Urchin Who Is Stalking Guinevere’s Scullery Maid

IV Camelot Estate Agent

V Exiled Journalist Disguised as Shrub

VI Arthur’s Crab-Boy Vision Faces Scalpel Practicalities

VII Crab Quotes

VIII You

IX Raving King Speech

X Lancelot’s Poetry Reading in Smoky Bar

XI Arthur, Arthur, Arthur…

XII A Disgruntled Knight

3 Sea Bed

Damage

This Was All About Me

2:19 to Whitstable

Break-up Party

Two Cents

Run

Sea Bed

Public Detectives

Facts

To Whom It May Concern

Screening

The Promises

Say When

Kissing

What Shall We Do With Your Subconscious?

Limerence

Medicine

Izzy

Conqueror

Atheism

I’m Sorry This Poem Is So Painful

The Stock Exchange

The Last House

The Fun Palace

Marriage of Equals

Corine

About the Author

Also by Caroline Bird from Carcanet Press

Copyright

1

Mystery Tears

Everything I touch is turning to gold – well, not real gold.

– Frank Kuppner

Sealing Wax

Sometimes I think of you,

my funny prodigy

and, like an ashtray on a Bible,

I pose here defeated,

singing ‘Lust’s most sacred impulse

is error!’ to a lean, dark and handsome

hat-stand. I find my head is able

to process a lifetime of gin, carping

‘My abuser can be so capricious!’ at social workers.

My phone-line is coy as the pale string

unspooling from the back-

end of a goldfish, elsewhere in an empty house.

Sometimes, my stable friend,

I think of you and whether

your bedroom was warm through the winter

and who’s spreading vapour rub on your chest.

Username: specialgirl2345

Some people call me The Ash Woman,

or Gjest Haraldes, the royal jailbird, and I’ve been

compared to Peter Christen Baardsen, the philandering

pianist. I have never been to Oslo. I have never set foot

in Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim. In fact, I’ve never been

to Norway. But some people call me Codeine the Wanderer.

Some people call me Duchess Mary Adelaide of Speck

or Queen Maud of Lancaster Gardens, I arouse deep rushes

of ceremonialism in women of low rank. In campfire songs

I am named the cult of Vesta. I’m not a cult. I’m a small person.

I rarely leave my room. But some crooners call me Smack the Wife.

Some people call me The Red-Handed Virgin, Sheeba of Dorwich,

Jack the Lamp. They say I had a morganatic marriage to a hobo,

he was buried with his trolley and I didn’t inherit one tin-can.

In folklore, I’ve become Nay Winkatmen – the very standoffish

prostitute. I am not the saviour of modern thatching

the locals of Wrafton near Brauton in North Devon think I am.

The Jewish Rastafarians call me Shrunken MC

for the beatific cakewalk of what used to be – in my youth –

the Crystal Methodist Church, some people call me Rabbi Marley.

I am not religious. I have no guiding star. Yet the Vatican engraved

Child of Jilted Joseph on an apostle spoon, jammed it in my sorbet.

My equestrian statue in northwestern Kazakhstan, facing

the Ural Mountains, remains nameless and free-roaming.

Some radio journalists are convinced I am the author of the quote

‘Bliss was it that dawn to be alive’ and then committed suicide.

They call me Irony Jane. I can’t remember the last time

I combed my hair, let alone spoke, but the paparazzi call me

The Flash Gazelle. Farmers call me Baby Burdock

and, as a newborn, I was baptised by the silent movie ghost

of Leopoldine Konstantin who mouthed the words

Dear Elvina, thus I’ve met you once before

subsiding with the harpsichord into the floor.

Mothers

I thought I was the child in this scenario.

I played the child and you loved me.

I did a grumpy face when the university

took Mr Teddy Rag-Ears,

I got words muddled like, ‘I stood very truck

as the still went through me.’

But then today

my future child called me on the telephone

and said, in a squeaky voice, ‘My mum is dying,

can you come over, I need someone to talk to.’

I didn’t know where my future child lived.

I had a feeling she was called Bertha

which disappointed me.

‘I live in south east west London,’ she said,

‘Where the spies and the cleaners live.

It’s spotless and seemingly empty.’

On the way over, a terrible pain ripped

through my stomach and I distantly

remembered a woman from my

adulthood I hadn’t seen since

that bed-wetting dream.

I passed glass conservatories on Bertha’s street.

They were acting as gallows for hanging plants.

‘I like that image,’ says Bertha, knotting the ties

on my hospital gown, shooing me out: ‘I told you

no more running away from hospital, didn’t I?’

Bertha, I went straight back. It’s disappeared –

all except the scout-hut used for art therapy

that whiffs a bit. This is my picture of mummy:

that is a tree because she’s in a forest, those are

mummy’s pink gloves and that’s an axe.

Snow Hotel

I

‘It is time for us to get out of Switzerland’

you announced and I couldn’t have agreed more

since we were not in Switzerland and my feet

were suffering in the clogs. My right hand

had been shot away in Bavaria and I refused

to employ my left hand for personal reasons.

We had moved to the fifth storey of the hotel.

Your chauffeur sang a message up the drain-pipe:

‘There are many exciting opportunities arising

in the glove compartment,’ which was code for

‘Love has vanished from the world, better jump.’

I pulled the rip-cord of my winter parachute,

waved in the brusque air, like a strangely lovely

fevered shiver. People were still on the streets.

It was quite funny the way they’d carried on speaking,

standing outside burger joints, re-enacting a chat,

puffing on a ‘fag’, pretending to breathe – you have

never seen smoke so tremulous in its falling lace.

II

The following week you were passing moist-eyed

beside the once beleaguered lime chapel, moaning

about being typecast, ‘I never even cry. My eyes just

get moist. Moist is the extent of my emotional range.

It’s such a joke.’ A guileless portico stuck to the face

of a filthy building dripped with rain: everything

was begging for love (women, harbours, plastic,

grapes, nuclear power plants, gym teachers) and

black tooth-marks were frosting the unused joints

of my left hand (which was not my helping hand,

although my right hand was declared a saint after it

was chopped off in Bulgaria) as your lips shaped out

‘The sixth storey of the hotel would suit us perfectly.’

I had a suspicion we were crossing into Switzerland.

Unacceptable Language

Any similarity to persons living or dead is

purely coincidental, apart from Andy, you cunt,

there was never a house in St Tropez. Do you

realise Greta used a toasted sandwich machine

to straighten her hair? As for Sue, she can sod

off back to Norwich, all she ever did was whine

and moan about her abusive parents: so they hit

her with a bath loofah? Jemima was murdered

by those toffs, she swears she wasn’t, but I’ve

seen her blue and bloated head buried in their

books. Gorgeously unclean, the twins are really

just one woman called Angela: some evenings

she thumbs me like a Holy Bible or Koran

or whatever, but mostly lies about stupid things

like can-openers or where the treasure is. Saul,

what were you thinking? She gained a degree

in avoidance addiction: seduce, revel and flee.

Jean needs a married man. She’s not like you, Saul.

Where’s your backbone, Florence? Being gay,

shouldn’t you curb your racism? Perhaps rivers

don’t flow like that, perhaps Dominic was right:

that baby belonged to nobody, it was a hoax,

a hoax in a pram to beguile him into empathy.

Empathy? That’s a consumer tool if ever there

was a Mecca, which there isn’t, otherwise what

are we doing in the supermarket? Meet me in

Greenwich village, Delilah, and we’ll recreate

the sixties. Burn this bra. Is that right? No, burn

this chair. Is that right? What are we supposed to

burn again? I arrived for the revolution with my

lunchbox. There were sheep. You people promised

to be my loud generation. I regret everything.

Derek is a contented dentist.

Mystery Tears

A poem about hysteria

You could order them from China over the Internet.

The website showed a grainy picture of Vivien Leigh

in Streetcar Named Desire.

It was two vials for twenty euros

and they were packaged like AA batteries.

They first became popular on the young German art scene –

thin boys would tap a few drops into their eyes then

paint their girlfriends legs akimbo and faces cramped

with wisdom, in the style of the Weimar Republic. It was

sexy. They weren’t like artificial Hollywood tears,

they had a sticky, salty texture

and a staggered release system. One minute,

you’re sitting at the dinner table eating a perfectly nice steak

then you’re crying until you’re sick in a plant-pot.

My partner sadly became addicted to Mystery Tears.

A thousand pounds went in a week

and everything I did provoked despair.

She loved the trickling sensation.

‘It’s so romantic,’ she said, ‘and yet I feel nothing.’

She started labelling her stash with names like

For Another and Things I Dare Not Tell.

She alternated vials, sometimes

cried all night.

She had bottles sent by special delivery marked

Not Enough. A dealer sold her stuff cut with

Fairy Liquid, street-name: River of Sorrow.

Our flat shook and dampened. I never

touched it. Each day she woke up

calmer and calmer.

Method Acting

(sorry, Chekhov)

I was Nina from The Seagull

while everyone was just getting on with their lives.

‘I am a seagull – no – no, I am an actress’

I’d say, then I’d weep. I was politely asked

to leave several Early Learning Centres.

There was no lake to wander by

so I drifted about by the fish counter in Tesco.

‘Am I much changed?’ I asked the woman.

She could not reply. ‘Your hair-net

is the most melancholy thing I’ve ever seen,’ I said.

I meant it as a compliment. I was asked to leave.

‘God take pity on homeless wanderers,’ I’d say

to a parked Land Rover, then I’d weep.

There was a young theatre director who loved me.

He stood like a beggar by the pick and mix section

of Cineworld. ‘Why do you say that you have kissed

the ground I walk on?’ I’d say, ‘Would you kiss

the gridded stairs of an escalator? Would you kiss

a red stain on the floor of a crisis shelter?’

Once, in a summer pub – ‘The Swan’ perhaps

in Stratford or ‘The Seagull’, no, that’s not right –

an older man squeezed lemon on my scampi.

Oh, older men! ‘Your life is beautiful,’ I said.

He drank his bitter ale like Agamemnon.

He told me a knock knock joke. My head reeled.

‘To one out of a million,’ I flirted, ‘comes

a bright destiny full of interest and meaning.’

‘You are very young and very kind,’ he laughed.

I forgot all about my Cineworld boy.

My spirit grew. My face thinned.

Years later, in a peasant-class carriage

of Virgin Rail, I tried to recreate that joke.

It was something about an interrupting sheep,

an interrupting seagull – no – no, that’s not what I meant.

My gestures were heavy and crude.

I cried Scwark instead of baaaaaaa. The pain!

The peasants pursued me with compliments but

I knew, by then, I was not golden. Some people

are built for greatness: they can tell a knock knock joke

with torrents through the heart. Have you forgotten,

Constantine, our childhood days of paper-rounds

and swiped milk-bottles? A kestrel for a knave…

A seagull – and yet – no.

‘I love him. I love him to despair,’

I told the chemist. She gave me Strepsils.

Sometimes, I was beside myself with the possibility of fame.

I stood in Dixons and smiled, pointing at the shiny laptops.

I imagined I had been employed in a Dixons’ advert.

I imagined I was on a television screen

with a million people watching.

My older man knew the managers of many department stores.

They did not want me for their adverts.

Not with my hollow eyes.

I started to dream, every night, of my Cineworld boy.

I dreamt he handed me a hotdog without recognition.

His eyelids were swollen like closed mussel shells.

Minutes after, I’d hear a popcorn machine explode

in a back room, grey butter everywhere. I am a seagull.

I am definitely a seagull. I saw Trigorin one last time

through the French windows. He was as handsome

and unapproachable as that first day. Still telling the same

knock knock joke, the same inspiration endlessly.

The Hat-Stand Union

The Hat-Stand Union